Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

The Things We Carry: On the Strength of the Army

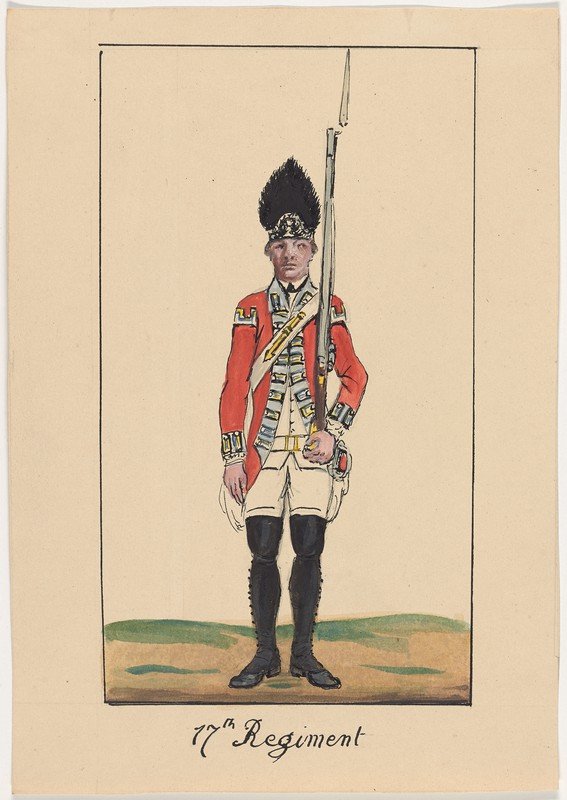

A couple weeks ago we had a member of the 17th Regiment of Infantry, Damian Niescior, write about all the things he carried during a weekend in the 18th century as a soldier in the British Army... this week we have a follow up post brought to you by Carrie Fellows, who has been working and recreating 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years. A year or so ago Carrie did a symposium with Kimberly Boice's: Historie Academie, which I happened to attend where she did a talk and workshop on how to pack for an event. So upon request it reminded me that she'd be the perfect fit to talk about what a follower of the army would bring with them.

Read Damian's blog post here.

- Mary S. an attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry

It can be difficult to explain to people what I do for fun. I combine my passion for history and the outdoors by interpreting the lives of women who, out of necessity, followed the Continental Army (and occasionally, the British army) during the American War for Independence. I have portrayed a laundress, an officer’s servant, a refugee, and a soldier’s wife, but regardless of whom I portray, the things I carry with me may vary slightly according to season, but remain essentially the same. Over the years, I have refined and limited the number of objects I carry, lightening my load for travel on foot over long distances, rough terrain, and the occasional river ford.

Records of what women carried are practically nonexistent, but one can find clues in runaway ads, military records, and the occasional primary source. Women attached to the army had only what they brought away with them, or acquired on the road. Women “on the strength” of the army were entitled to a half-ration of food (children received a one-quarter ration.) I am always hungry, and as rations aren’t always available, carry enough food to get by.

Tied about my middle, under my gown, a pair of pockets (1) is suspended. These contain both modern items (pocket on right) and period ones (pocket on left). I often leave my phone in the car unless I need to take photos for a talk or article, or will be in the deep backcountry.* My car keys (40) are pinned firmly to the inside bottom corner of my left pocket. In my right pocket: a sewing kit (2) or “housewife” – a roll of cloth with pockets to hold sewing supplies and tiny items like sleeve buttons, also a linen handkerchief (3), pocket knife (4), linen or woolen mitts (5), period scrip and real cash in a reproduction pocketbook (6), lip balm in a tin container (7).

I carry most of my gear in a wallet (8) – a rectangular cloth bag with a slit opening in the center. One places items in each end, then twists the entire thing at the center, closing the slit and forming a kind of narrow strap, then slung over the shoulder. I try to segregate the two ends into food/related items and clothing/personal items. The food side holds a small bag of cornmeal or rice (9), cheese wrapped in 2 layers of linen (10 - the inner one dampened with vinegar); a cured sausage wrapped in brown paper (11), a small bag of walnuts (12), bread (13), tea (14), salt (15), seasonal vegetables (16), a spice bag, grater, candle ends and extra corks (17), paper packets of flour and pepper (18), and sometimes I even remember my fire kit: flint, steel, charcloth and tow in a tin box (42). Food-related items include a turned wooden bowl (19), which can serve as both drinking and eating vessel, an eating spoon (20), and a linen towel (21).

In the other end, I carry extra clothing items tied up together in a large kerchief (22): moccasins (23) and a man’s wool cap (24) for sleeping in, stockings (25), neck handkerchief (26), and a small paper notebook (27). Some also carry a clean shift, but I do not, as I am rarely in a situation where there is privacy sufficient change it. Also: a tiny modern first aid kit in a red linen bag (28), personal toiletry items in another small drawstring bag: a tin box with soap and mirror (29), horn comb and bone toothbrush (30), handwoven wash towel (31), spectacles (32), allergy meds &, contact lens case (not pictured). Reenactor etiquette requires one to manage any non-historic personal care out of view as much as possible. Optional items, depending on the planned activity: a small bundle of mending patches and yarn (33), and a darning egg (34) to occupy time and to trade (mending skills have value), a large wooden cooking spoon (35), and a small axe (36). If there’s room, “luxury” items include a ceramic cup (37) and a big linen wallet that doubles as a straw tick (38).

I usually carry just one blanket (with a wool petticoat and cloak inside) rolled up, tied together at the ends to form a “U”, and carried across my body. I put on the wallet first, then the canteen (39) - the wallet cushions the strap - then the rolled blanket over that. The blanket helps keep both wallet and canteen secure, close to my body, and quiet as I walk – or run.

The last thing I pick up is my small iron pot (41), with its sheet iron lid tied on so it doesn’t rattle or become lost. If I have eggs or fruit, I pack it in the pot. It goes to every event with me. I hadn’t thought about it before, but that little pot – representing security, hot food, comfort (and home?) connects me to the women I portray who carried what they most valued when they followed the army.

*Nothing ruins an accurate setting faster than when the smartphones come out and glow blue at night.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

CARRIE FELLOWShas been interpreting 18th century domestic arts for more than 25 years and is the Sergeant of Women for the progressive living history group, Augusta County Militia. She has held positions in history nonprofits and museums as a curator, educator, director, and board member, and is currently the Executive Director of the Hunterdon County (NJ) Cultural & Heritage Commission. She and her husband Mark are addicted to old houses.

The Malicious, Morose Malady and the Vindictive, Vagrant Vixen: A 17th Regiment Story, Part 2

In this week's blog entry, we return to finish the tale of Private Thomas Mallady's post-war adventures, initially chronicled this past May by guest author Don Hagist. While the documentary trail might not give us all the information we could hope for, there are some clear messages about the nature of marital disharmony in post-war New England that should give any would-be deserter food for thought. For more soldiers' stories, check out Don's blog: British Soldiers, American Revolution.

Click here for Part I

-- Will Tatum

Part II

The next week's issue of the Western Star, on 18 September, carried Thomas Mellalew's response, this time datelined from Pittsfield:

"To the Publick.Whenever the character of an individual is notoriously attacked, it is incumbent on him, if he has any regard for his reputation, or respect for the opinion of the world, to come forward in his own defence. The writer is sensible that a private controversy between a man and woman, is not a very pleasing subject for the attention of the community: His only excuse is, that he write in his own defence.

"In the Star of last week, was published a piece under the signature of Hannah Mellalew - a performance in which my character is represented as black as the pen wielded by the hand of falhood [sic] could possibly describe. A publication, signed by a woman, the blackness of whose character my modesty will not permit me to lay naked to the view of the world - a woman with whom had it have been possible for any man to have lived, would not have been under the necessity of strolling about after a second gulled companion, while the first was still living. Let any ingenuous mind read the performance to which I allude, and then say, if any but an abandoned prostitute could ever have come forward with such a publication in the face of the world. No, not a woman on earth, who is not totally devoid of every species of virtue, could have assumed the impudence to publish such brothel ideas of a man, whom she claims as her companion.

"The charges alledged against me in that piece, it is in my power, at any time to confute. But I do not conceive that a Newspaper is a proper place to produce affidavits to establish the character of any man.”

"Neither do I believe that the publick are so strongly inclined to believe any man a villain, as, without proof, without witnesses, or even the appearance of truth, to give credit to the aspersions of a malicious, vindictive, vagrant vixen. Thomas Mallady.Pittsfield, Sept. 1792."

It didn't end there. The next week's issue of the Wester Star, dated 25 September, contained Hannah's next volley, this one a barrage including statements from other individuals:

"To the Publick.Thomas Mallady (or Mellalew) having asserted in the paper of last week, that the charges I have exhibited against him are not true, the following are submitted to the inspection of the publick. Hannah Mellalew.

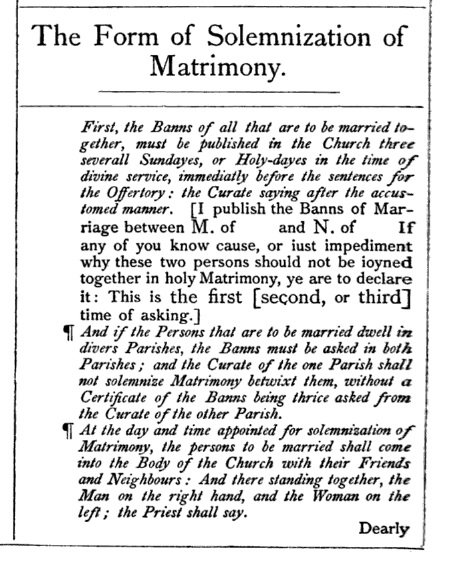

"Middletown, February 18, 1778."These may certify that Thomas Mellalew and Hannah Andrews were married on the day of the date above, according to the form in the office for the solemnization of marriage, in the book of common prayer, by me, Abraham Jarvis, Minister of the Church of England.

"These may certify whom it may concern, that Thomas Mellalew (or Mallady, as many persons called him) some years since lived in this town with his wife; and, while he lived in this town, he advertised his wife in the Springfield Newspaper, lest she should run him in debt when he was absent; and afterwards put in another advertisement, wherein he manifested his sorrow for the first, and said he had no foundation or just cause for publishing the first.

Furthermore, while he lived in this town, he made an appointment to meet a Negro's wife, at a certain place in the night time, in a certain barn; and the Negro's wife informed Mrs. Mellalew of the appointment, who procured sundry persons, one of whom was dressed in a woman's clothes, to meet at the time and place appointed, when and where Mellalew attended in the dark, and his conduct was such, as caused them to lead him home to his wife; and he did not deny his intent in going to the barn, and in the barn called the Negro's wife by name several times, before the persons lying in wait discovered themselves. The substance of the above was sworn to before me, as nearly as I can recollect, by two of the persons who were in the barn, and one of them who was dressed in women's apparel.

P. S. Mrs. Mellalew's character in this town is good, for any thing that I know.

Samuel Mather, Justice of the Peace.Westfield, August 17, 1792."

The story certainly didn't end there, but unfortunately our documentary trail does. Further research might reveal what became of this former soldier of the 17th and his estranged wife, and help us decide whether he was "malicious and morose," or she was a "vindictive, vagrant vixen."

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books.

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books.

The first, British Soldiers, American War examines the Revolutionary conflict through the eyes of British soldiers’ narratives. The second and more recent is The Revolution’s Last Men, an exploration of the last veterans of the War for Independence who were captured through early photography. Hagist runs his own blog and is a regular contributor at the Journal of the American Revolution

The Things We Carry

First of all happy Wednesday! Before we get into today's blog post I wanted to mention that we have a news letter that will be starting to send out every Monday in June! So if you haven't yet signed up for the newsletter please feel free to do so. No spam, just 17th updates and a few short history lessons.

Now this week on the blog we have a Damian Niescior, most of you may know Damian from his work experience at Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York, but now he serves as a Gallery Educator at the new Museum of the American Revolution in Old City, Philadelphia, PA, continuing to chat history to visitors. This blog post has been requested by some readers and is very informative in everything that Damian carries on his person to events has a purpose, can be easily stowed away in pockets, haversacks, and knapsacks, and nothing is there "just for looks". Enjoy the read!

Mary Sherlock - A follower attached to the 17th Regiment of Infantry

“They carried the sky. The whole atmosphere, they carried it, the humidity, the monsoons, the stink of fungus and decay, all of it, they carried gravity.”― Tim O'Brien, The Things They Carried

Throughout my time as a historical interpreter, both amateur and professional, I have been asked a fair amount on what I carry and why I carry it. I find it’s important to represent the soldiers as best we can as individuals, which includes minute details that may not even have a chance to see. These items also allow me to be self-sufficient while at events, keeping myself from needing to return to a vehicle. These items are both small and large, but all carry some significance to the interpretation of soldier life on campaign.

- The very first thing put on is the bayonet belt. It carries the sidearm, the bayonet, a triangular shaped blade of about 18 inches long. It is supported by the scabbard which sits in the belt itself. The buff leather belt is based off of several surviving originals, and although it is a waist belt, it is worn across the shoulder as a field modification to improve comfort.

- The next item we put on is the cartridge pouch. This pouch is a soft leather bag sewn with a hard leather flap to protect the cartridges inside. The cartridges sit in a wooden block, nailed into place by a series of small iron tacks, and can hold 21 cartridges. The white shoulder strap is, like the bayonet belt, made from buff leather. This pouch is of an older style, originally designed and used during the 7 years’ war, but then with a wider strap and extra square buckle. The pouch was modified to conform to the Royal Clothing Warrant of 1768. The 17th, months before the start of the war in 1775, ordered new cartridge pouches in an effort to replace the older outdated ones they were still carrying. Through the orderly books, although they had ordered the new pouches, they did not arrive in time for the 17th’s voyage to America in mid-1775.

- Over the buff accoutrements, camp equipment is then placed, starting with the haversack. The haversack is a coarse linen bag, closed with two buttons on the side and suspended by a strap made from the same cloth. Its job is to hold the rations of each individual soldier. These rations were issued out once per every three days, which could include daily rations of one pound of flour or bread, one pound of beef or one half pound of pork, one quarter pint of peas, and one ounce of rice.

- Next is the canteen. The canteen is made from tinned iron, and suspended with a thin hemp rope. To help prevent rusting, beeswax is melted inside the canteen and shaken around to coat the interior. The canteen itself is made after an original, which had a tin cap for the spout as well. I, however, lost that cap a long time ago, and have since been replaced with a cork.

- The musket is the Short Land pattern, or second model, and also known as the Brown Bess. This musket is made from walnut, iron, steel, and brass. It features a 42 inch long barrel and its total weight is eight pounds. Completed with a buff leather sling to finish the look and assist with the carrying of the gun itself.

We have now reached the knapsack itself, which has many items inside it, each one I have carefully chosen to represent what a British soldier might carry in their pack.

- The knapsack itself is of a simple construction. It is primarily a hemp linen pack with two large pockets on each half. Each pocket is closed with two buttons made of pewter. The exterior of the knapsack is painted to repel rain and other weather. The knapsack is closed by three leather straps with conjoining buckles, and the pack itself is worn on the back with two shoulder straps made of leather as well. In the bottom half of the pack I keep tools and utensils, and clothing in the top half of the pack.

- An extra pair of shoes. At the height of the war, Britain was shipping nearly 40,000 pairs of shoes to supply its army with 2 pairs of shoes per man, per year. As I wear one pair of shoes on my feet, the others sit in my knapsack. There does seem to be some great relief when putting on dry shoes after walking in wet shoes all day.

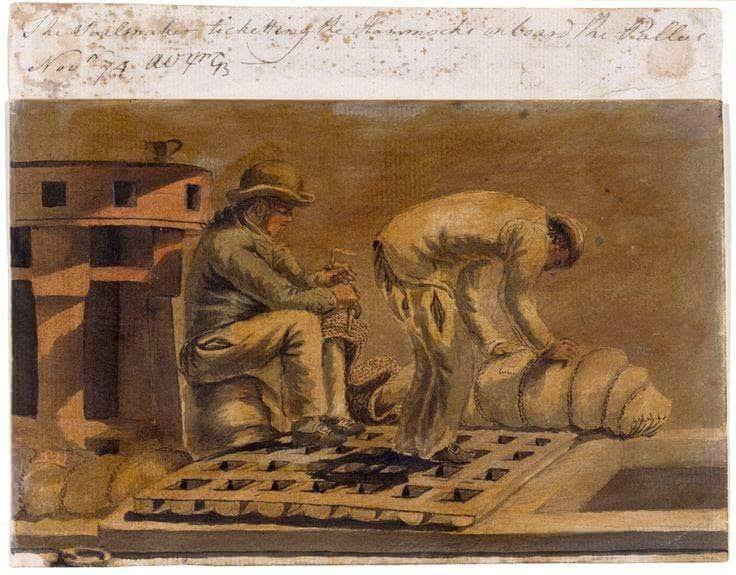

- Shoe tools; a hammer, lasting pliers, a set of pincers, leather palm, and awls wrapped up in a leather apron. While I was an interpreter at Fort Ticonderoga, I was an apprentice shoemaker studying under Mr. Pekar. Under his tutelage I developed some skills as a shoemaker, including the ability to repair shoes that had needed new soles and heels. The British army of the 18th Century contained a great deal of tradesmen, and many of them were shoemakers. These shoemakers, although soldiers first, facilitated the repair of shoes in the army.

- Donation soles. These soles, bound together with a simple tie, were issued to each man for each pair of shoes. It is typical for the average soldier to wear through soles in 3 months, but with two pairs of shoes per year means that the average soldier will wear each pair for six months. In order to bridge this gap, the British Army provides enough replacement leather for new soles and new heels for each pair. This is not in the assumption that each man has the skills required to repair his own shoes, but in the assumption that, due to the prolific nature of the shoemaking trade, each man will know a shoemaker in their own mess group or company willing to do the work.

- In order to keep the shoes I carry both presentable and healthy, a black polishing agent known as blackball is kept with my other tools. Blackball is a combination of charcoal, tallow and beeswax. The substance itself, when properly applied, returns a black finish to shoes while also keeping the leather from becoming too dry. Each soldier was issued an amount of blackball to maintain the shoes and black leather pouch.

- A small folding knife. This small folding knife has assisted me in more ways than I can mention. It has been a tool in cutting leather, a cooking utensil, a screwdriver and several other useful applications throughout the years.

- A pocket watch. Watches are especially useful to the life of a soldier. Although 18th century watches are impossibly complicated and expensive today, in the 18th century they were commonplace.

- Extra cartridges carried in a small brown package. In order to keep myself self-sufficient as the British Army could be, in addition to the 21 cartridges I carry in my pouch, I also carry additional ammunition in my knapsack.

- Musket tool. This reproduction of a musket tool is based off an original, and is used to maintain the musket. The tool itself is the only device needed when disassembling a great majority of the gun itself.

- A wooden bowl and pewter spoon. For my own comfort, I carry my own eating utensils. Although individual soldiers did carry their own bowls, soldiers would also eat out of the same kettle, removing the need to carry a bowl while on campaign.

- A tin cup. This reproduction of a cup, found at a British army encampment in North America, is a useful item to have when in the field. It can serve as both a drinking vessel and as a small cooking utensil as well. While I’ll admit that some of the worst coffee I have ever had, has been made in that cup, it is also the best coffee I have ever had.

- Wallet and notebook. Two items I have found to help remove myself from the 21st century when I am in the field. The wallet holds any cash I might use to purchase goods while at events, and the notebook allows me to jot down any thoughts or any notes I can review later.

- A pair of dice and snuff tin. We can’t have a good soldier impression without some vices thrown in! The dice I carry allows me to partake in a very old game known as Hazard. This game was very popular with soldiers; it required only a pair of dice and an understanding of the game itself. The snuff tin carries a small measure of snuff tobacco. Snuff is powdered tobacco taken through the nasal passage in very small quantities. Due to its unique method of inhalation, often the public use of snuff can come with strange looks from visitors.

- Two pairs of stockings. Each British soldier, in order to keep feet dry and healthy, would carry a number of extra stockings. I carry two extra on top of the pair I would be wearing, in total three pairs. There is something to be said of the quality of dry socks.

- Neckstock, one linen kerchief, and one cotton kerchief. A British soldier of the period would have a few items of neckwear. The one worn while on parade or battle, would be the neckstock. This garment is made of black velvet and finished with a false white shirt collar. This garment provides the soldier with a clean, military look. When the neckstock was not worn, softer kerchiefs and rollers could be worn.

- Fatigue cap. In order to preserve and protect the cocked hat from unnecessary damage, a cap is worn instead. This cap is based off of description and a few pictorial representations in paintings of the period. It is kept in my knapsack when not in use.

- Two shirts. These two shirts, I carry based on orders issued to the 17th at various points during the war, consist of one white and one made of check cloth. Like the extra shoes and stockings, it allows me to change into dry undergarments. This is especially useful during the hot days which can leave a shirt drenched with sweat.

- Watchcoats are heavy wool overcoats which assist a soldier while posted on sentry or picket duty. The British army issued these to regiments as about one watchcoat per 6 men. These garments were shared, and made to fit most sizes. I can tell you from personal experience, that extra layer of wool is a boon when enduring difficult weather.

- Last but not least is the blanket. It is rolled up and attached with ties to the top of the pack. This allows the weight to be more manageable, and to keep the pack from becoming too bloated.

Each item is packed away carefully into the knapsack. Shirts are rolled up and pressed into the pack as efficiently as possible. The ending result is a tight, but efficient pack which weighs 20 pounds when fully loaded up. While these items all serve a purpose, each one a carefully chosen representative of items British soldiers of the period would have carried, this is as close I can come to understanding of what those soldiers would have endured. Those soldiers, serving thousands of miles away from home, would have carried a lot more than just items throughout the cities and wilderness of North America.

DAMIAN NIESCIORCurrently serves as Gallery Educator at the Museum of the American Revolution in Old City, Philadelphia, PA after serving as an interpreter at Fort Ticonderoga in Ticonderoga, New York. He has been reenacting and interpreting British soldier’s life since 2009.

The Malicious, Morose Malady and the Vindictive, Vagrant Vixen: A 17th Regiment Story, Part 1

This week we welcome British Army researcher extraordinaire Don Hagist to the blog. Don has spent many years researching the interior lives of the common British soldier, tracing his experiences, thoughts, and feelings throughout the conflict and beyond. In this installment, we receive a rare window into the post-war experiences of one man who chose to stay in America and made questionable relationship choices that places him in hot water. This is part 1 of the article, so be sure to tune in for part 2 next month.

- Will Tatum

On February 18, 1778, a wedding took place in Middletown, Connecticut. Thomas Mellalew married Hannah Andrews at an Anglican church in the little town on a big bend in the Connecticut River. We have no details on Hannah's background, but we wonder if her choice of a husband caused a stir in her family or community, for he was a British soldier. Or, at least, he had been, until he deserted from the 17th Regiment of Foot.

The surname is rendered on the regiment's muster rolls as "Melody," but as will be seen below, other spellings include Mallady, Mallalue, and similar phonetic variants. Nothing that we know about Thomas Mellalew's military career suggests that he was prone to abscond from the army, but we have little to go on besides the muster rolls, and his desertion was not an ordinary case. From England or Scotland (the muster rolls tell us that he was "British" as opposed to Irish or "Foreign"), he joined the army some time before 1772, the earliest date for which rolls exist. He had been a weaver before enlisting, the most common trade among British soldiers. No detailed records survive to tell us about his discipline or performance as a soldier, except that he was trusted enough to be granted a furlough during the regiment's peacetime years in Great Britain.

Mellalew came to America with the regiment in late 1775, and endured the difficult winter in Boston, the voyage to Halifax and then to Staten Island in the first half of 1776, and the fast-moving campaign through New York and New Jersey in the second half of that year. At the beginning of 1777 he had at least five years of experience as a soldier, including one major campaign.

The battle of Princeton on 3 January 1777 was perhaps the 17th Regiment's greatest trial of the war. In the face of overwhelming odds, the seven companies of the regiment engaged (the flank companies were detached, and it appears that one battalion company was some distance away as a baggage guard) acquitted themselves well. They did suffer a significant number of killed, wounded and captured. Among the latter was Thomas Mellalew. The Princeton prisoners were sent to Connecticut, where they were dispersed among several towns. Mellalew was sent to a small town in the northwestern part of the state called New Hartford. He didn't stay. He may have obtained permission to work locally, as many British prisoners did, or he may have simply had enough of soldiering. One way or another, he deserted from captivity, the next we know of him is his marriage in Middletown a year later and some 25 miles southeast of New Hartford.

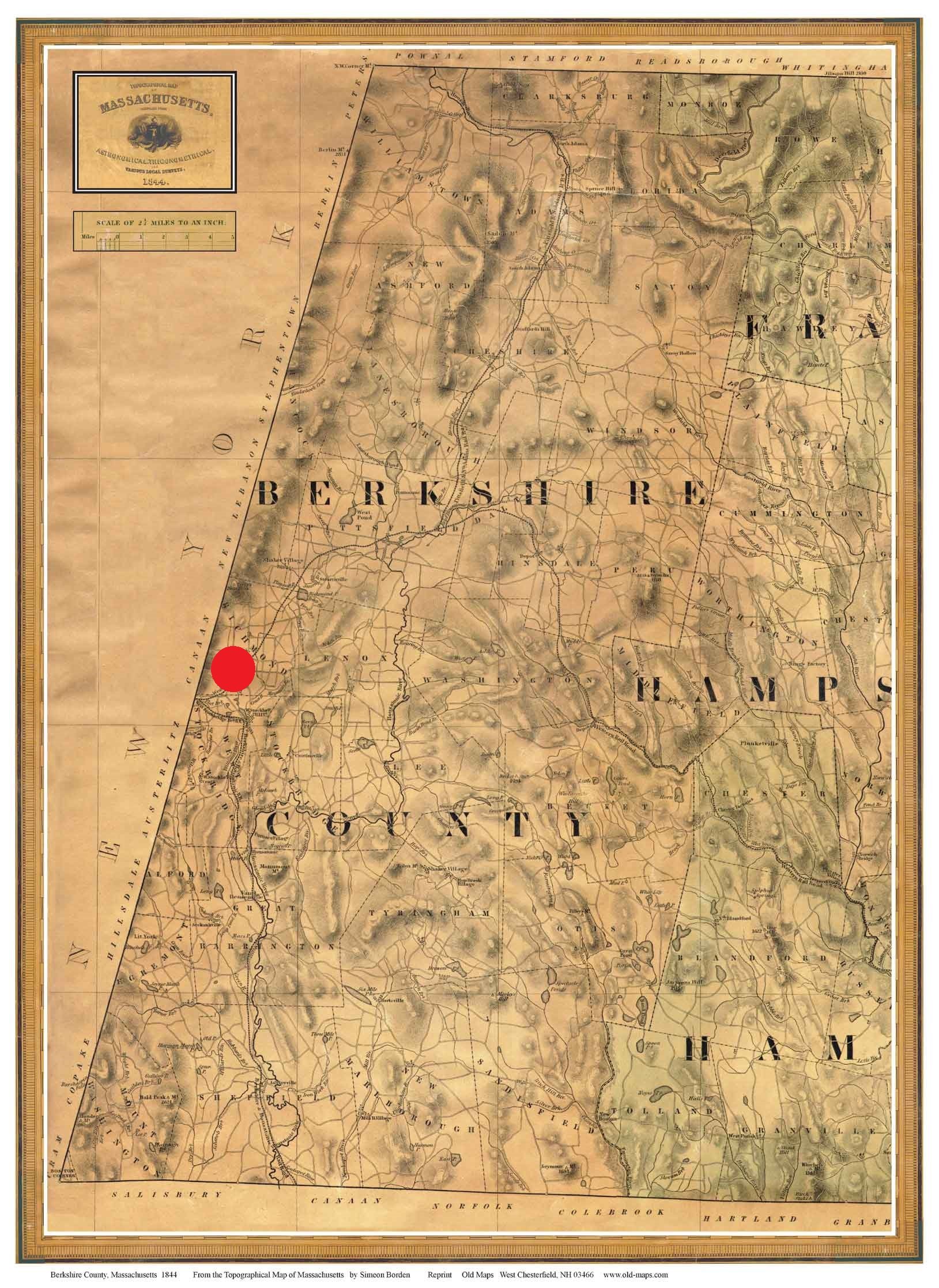

Their specific activities over the next dozen years haven't been determined. We know that he worked as a barber, a trade he may have learned in the army. In the 1780s they lived for time in Westfield, Massachusetts, just west of Springfield. He drank. He sought out other women. At some point he took an ad out in a Springfield newspaper. Soon after, he took out another ad rescinding the first one. We haven't found the text of either ad, but the first one probably looked something like this one, that he placed in the autumn of 1791: "Whereas Hannah, my Wife, has forsaken my bed and board - this is therefore to forbid all persons trusting her on my account. Thomas Mallady. Richmond, October 14, 1791."

The ad, dated from the Massachusetts town of Richmond on the New York border, was placed in the 25 October edition of a newspaper called the Western Star that began publication in Stockbridge, Massachusetts in 1789. Ads like this were fairly common in period newspapers, and usually we can only wonder about the stories behind them. In this case, however, apparently after considerable fallout from ad and other events, Hannah Mellalew published a notice of her own in the 11 September 1792 edition of the same paper:

"Take Notice.It is with reluctance that I am drove to the disagreeable necessity of publishing the subsequent lines for the consideration of the candid publick. I am sensible that publications of this kind often have a tendency to bring disgrace on the author; but all who have read the publication of Thomas Mellalew (or Mallady, as he calls himself) my Companion (who advertised me in the publick prints in the months of October last) will pardon me for being desirous that the publick should have a just statement of the facts. A statement of one half of the aggravated crimes that he was guilty of while we lived together would make a larger volume than I am able to get published, or any one have patience to read, and they would bring disgrace on me and all the human race; therefore, I shall only mention a few that are the least dishonourable. I can with prudence say, that they are such as these; taking property that was not his own; being with other women, of all characters but good, and all colours but white; he has once been detected in attempting to be with a Negroe's wife in a barn: It will be needless to mention drunkenness, it being so trifling compared with his other failings. It is not my power to describe his malicious and morose temper, but it is such that I lived in great fear of being murdered by him. If any persons should dispute the truth of these facts, I shall be very happy if they would take the trouble to call on me, to convince them of the truth of these and many others, (if they will have patience to hear,) by the best authorities where he hath lived; and likewise that I have conducted with as much prudence as any person could under my circumstances. The said Mellalew (or Mallady) is a Weaver & Barber, about middling size, has a scar on his upper lip, which has the appearance of a hair lip, sewed up; has black curled hair, is a foreigner that deserted from the British army last war. Whoever will take up said Mellalew (or Mallady) and conceal him from the sight of man and beast, shall have my thanks, and will merit the applause of the publick. All persons are forbid harbouring or trusting him on my account. Hannah Mellalew. East Hampton, Sept. 1792."

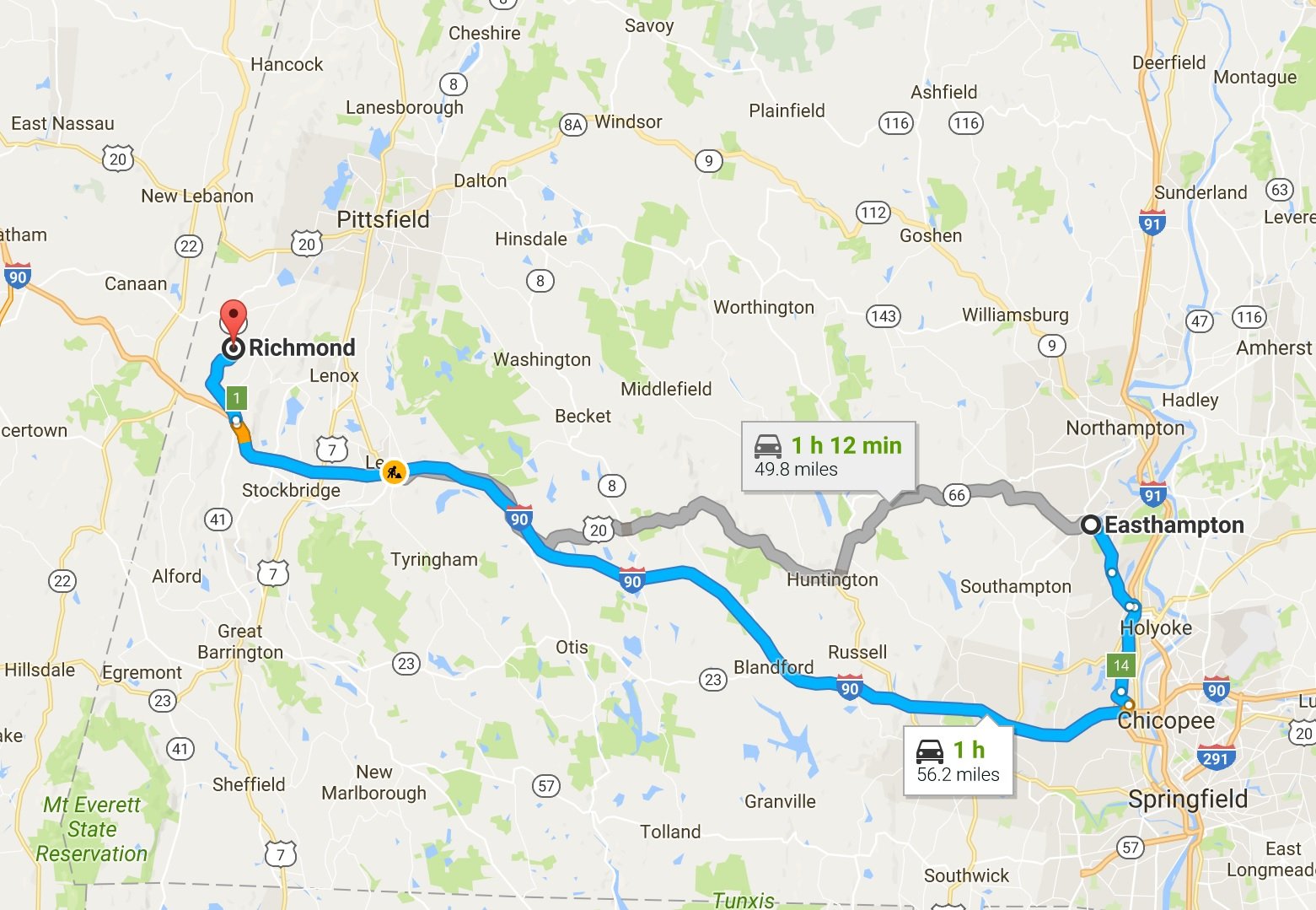

Easthampton is a considerable distance from Richmond, so clearly the couple had separated by this point. But they were reading the same paper. In fact, they were supporting it with ad revenue from their competing notices. The next week's issue, on 18 September, carried Thomas Mellalew's response, this time datelined from Pittsfield:

"To the Publick.Whenever the character of an individual is notoriously attacked, it is incumbent on him, if he has any regard for his reputation, or respect for the opinion of the world, to come forward in his own defence. The writer is sensible that a private controversy between a man and woman, is not a very pleasing subject for the attention of the community: His only excuse is, that he write in his own defence."In the Star of last week, was published a piece under the signature of Hannah Mellalew -a performance in which my character is represented as black as the pen wielded by the hand of falhood [sic] could possibly describe. A publication, signed by a woman, the blackness of whose character my modesty will not permit me to lay naked to the view of the world - a woman with whom had it have been possible for any man to have lived, would not have been under the necessity of strolling about after a second gulled companion, while the first was still living. Let any ingenuous mind read the performance to which I allude, and then say, if any but an abandoned prostitute could ever have come forward with such a publication in the face of the world. No, not a woman on earth, who is not totally devoid of every species of virtue, could have assumed the impudence to publish such brothel ideas of a man, whom she claims as her companion."The charges alledged against me in that piece, it is in my power, at any time to confute. But I do not conceive that a Newspaper is a proper place to produce affidavits to establish the character of any man."Neither do I believe that the publick are so strongly inclined to believe any man a villain, as, without proof, without witnesses, or even the appearance of truth, to give credit to the aspersions of a malicious, vindictive, vagrant vixen. Thomas Mallady."Pittsfield, Sept. 1792."

It didn't end there. The next week's issue of the Wester Star, dated 25 September, contained Hannah's next volley...[tune in for part 2 in a future installment!]

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books.

DON HAGISTis a life-long British Army researcher and founding member of the 22nd Regiment of Foot (recreated). His scholarly career includes preparing and publishing numerous editions of period primary sources and analytical articles for the living history community. Most recently, Hagist has written two major books.

The first, British Soldiers, American War examines the Revolutionary conflict through the eyes of British soldiers' narratives. The second and more recent is The Revolution's Last Men, an exploration of the last veterans of the War for Independence who were captured through early photography. Hagist runs his own blog and is a regular contributor at the Journal of the American Revolution

Captain William Brereton and the Grenadier Company: Officers of the 17th, Part 2

In this second installment of the series, Mark Odintz, Ph.D., returns with a look at the officers who served in the 17th's Grenadier Company during the war. As always, we are grateful to Mark both for choosing the 17th Regiment for his studies and for sharing the fruits of his labor with our readers. If you enjoy these and Mark's other entries, please post in the comments: we're encouraging him to transform his dissertation into a book!

- Will Tatum

In this post I will provide sketches of the three officers who served in the grenadier company of the 17th during most of the American Revolution, with the addition of two others who joined it in 1781. For most of the period of the war the regiment contained twelve companies: eight companies of the line; two specialist companies, grenadiers and light infantry, known as the “flank” companies; and two “additional” companies that remained in the British Isles recruiting and forwarding men overseas to the regiment. Flank companies were usually detached from the regiment during the war and served in separate battalions of grenadiers and light infantry. Their officer compliment consisted of a captain and two lieutenants, in contrast to the average line company, which contained a captain (or field officer or captain lieutenant), a lieutenant and an ensign. Enlisted grenadiers were chosen in part for their height and physique, though this probably became less important on wartime service, when qualities of steadiness, toughness and endurance were paramount. For officers, service in the flank companies was prized as a vehicle for furthering one’s reputation, career and professional expertise. Eleven officers served in the light company of the 17th during the war, reflecting its almost constant active service and high level of casualties. The grenadier company, in contrast, though it saw hard service in the field, was officered almost entirely by three men, William Brereton, Gideon Shairp (or Sharp) and Lawford Miles, with two others, Alexander Saunderson and James Forrest, serving for the final two years of the war. Of the five three were Irish, one Scots, and one American, thus highlighting the national diversity of the officer corps during the American War.

William Brereton, captain of the grenadier company of the 17th for much of the Revolution, is a classic example of the commitment of the Protestant Ascendancy of Ireland to military service. He came from a family of Anglo-Irish gentry that had come over to Ireland from Cheshire in the 16th century. His grandfather, William Brereton of Carrigslaney, County Carlow and Lohart Castle, county Cork, had served as High Sherriff of County Carlow in 1737. Our William’s father, Percival, was the third son, and died a captain in the 48th Foot with Braddock in 1755. Four of William’s uncles also served in the army, and his mother, Mary Lee, was the daughter of a general. A letter from William’s uncle Edward to Lord Amherst, soliciting a company for himself during the American Revolution, demonstrates the family ties to the military and how the connection had carried over into the next generation. He laid out his service and went on to state he “had 4 brothers officers, one of whom was killed with Braddock, and now 3 nephews in the Service.” (Burkes Family Records, Brereton Family; WO34:154, f. 147 Edward Brereton to Amherst).

William was born in 1752 and purchased an ensigncy in the 17th on August 2, 1769. When Captain Edward Hope died in 1771, the succession went without purchase and Brereton became a lieutenant on Nov. 14, 1771. He became adjutant by purchase of the 17th in February, 1775 and continued to serve as adjutant until April of 1777. He purchased the captain lieutenantcy of the 17th on May 24, 1775 and purchased his captaincy later that year. He was commanding the grenadier company of the 17th by July of 1776 and, with the exception of a brief interval in July of 1780, continued to lead the grenadiers until he was promoted out of the regiment in April of 1781. (Record of service in WO25:751, f.217; dates of service in grenadier company from the rolls in WO12).

He was clearly an outstanding combat soldier, and distinguished himself during his six years as commander of the grenadier company. In 1779 his former commander, Earl Cornwallis, recommended him for promotion by summing up his service in the 17th- “He did his duty with the greatest spirit & zeal during the three campaigns in which I commanded the Grenadiers, but he more than once stepp’d forth when not particularly called upon, and without the too common apprehension of taking responsibility upon himself by his courage and good sense render’d essential service…” (WO1:1056, f. 317). One of his bolder exploits involved the capture of an American frigate, the Delaware, during the Philadelphia Campaign. On September 27, 1777, the thirty-four gun ship was attempting to deny the Delaware River to British shipping when it ran aground. A mixed force of British marines, sailors and Brereton’s grenadiers captured the ship, refloated it, and incorporated it into the Royal Navy. (Webb, Services of the 17th Regiment, pp. 73-73; Taafe, The Philadelphia Campaign, pp. 112-113).

Perhaps the high point of his service as a grenadier came a few weeks later on the morning of October 11, 1777. An outpost on an island near Philadelphia under the command of Major Vatass of the 10th was surprised by a rebel force. Acting quickly and without orders, Brereton and Captain Wills, a grenadier officer of the 23d, put together a scratch force of grenadiers and Hessians, crossed over to the island, recaptured the post and rescued the garrison as it was being brought off by the rebels (WO71:84, Court-martial of John Vatass, 16 Oct 1777; and Court-martial of Richard Blackmore 21 October 1777). Continuing at the head of the grenadier company, Brereton was wounded at the battle of Monmouth in 1778.

After twelve years in the 17th Brereton purchased his majority in the 64th Foot in April of 1781. Late in the war Brereton commanded at one of the last successful British skirmishes of the war at the Battle of the Combahee River, outside Beaufort, South Carolina. On August 27, 1782, he was leading a foraging detachment (including a company from the 17th) from the garrison at Charleston when they were intercepted by an American force under Mordechai Gist and John Laurens (now of Hamilton the musical fame). Brereton ambushed the rebels, killing Laurens, capturing a howitzer and, after further skirmishes, returned to Charleston. He became a lieutenant colonel by purchase in the 58th Foot in 1789, and retired in 1792. Like many other retired officers he made himself useful during the lengthy crisis of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars by holding a number of other military appointments; serving as paymaster for a recruiting district, as an officer in the Wiltshire Militia, and as inspecting field officer of yeomanry for the Western District.

In 1784 William Brereton married Mary Lill, daughter of Godfrey Lill, Judge of Common Pleas for Ireland. Of his three sons who survived into adulthood, one entered the army and two served in the Royal Navy, continuing the tradition of military service. He lived at Chichester in England during his final years and died in November of 1830.

Gideon Shairp served as lieutenant of the company for the entire war. He came from a family of lowland Scottish landed gentry, the Shairps of Houston, co. Linlithgow (modern West Lothian). Born in 1756, he was the second son of Thomas Shairp, of Houston, whose children followed the classic pattern of gentry with strong ties to the services. Thomas, the eldest, inherited the estate, married and produced heirs; our Gideon entered the army, the third son went into the Royal Navy and the two youngest went into the army as well (family info from Burkes Landed Gentry, 1853, p. 1222 Shairp of Houston). Gideon purchased an ensigncy in the 17th on August 31, 1774, and was assigned to the grenadier company in August or September of 1775. As part of the augmentation of the army he was promoted to lieutenant without purchase on August 23, 1775 and served as the senior lieutenant of the grenadier company from 1775 through 1783. He purchased his captain lieutenantcy on Sept 14, 1787, became captain a month later and after twenty-one years in the 17th was promoted out as major to a new corps in May of 1795. He shifted to a more stable berth as major to the 22nd Foot in September of the same year and became lieutenant colonel to the 9th Foot in August of 1799. Gideon was serving as quartermaster general of Ireland at the time of his death in 1806. As far as I can tell, he never married. In his will he leaves his estate to his brother Walter, his baggage to his servant, and a ceremonial sword presented to him by the officers of the 9th to his friend, Major General Browning. (PCC Will proved 1806).

The third grenadier officer is another Irishman, Lawford Miles. His family was minor gentry in County Tipperary. His father, Edward Miles, gent, of Ballyloughan, died in 1778, leaving six daughters and five sons. At some point our Lawford inherited the estate of his uncle in Rochestown, and the family also owned land at Clonmel and Clogheen, all in Tipperary (Irish Wills, p.349; online list of Tipperary freeholders 1775-6) He entered the 17th as an ensign without purchase on May 1, 1775, and became a lieutenant, also without purchase, on September 8, 1775. He was serving as the junior lieutenant of the grenadier company by July of 1776 and served in the company at least until February of 1781. Miles purchased his company in the 17th on April 29, 1781 and was serving with the main body of the regiment at the surrender of Yorktown. He was the only captain chosen to accompany the regiment into captivity, and found his time as a prisoner had its dangers as well. He “was also one of the capts for whom the Americans drew lotts when Capt Asgill of the Guards was the unfortunate person” (WO1:1024 f. 775, Lawford Miles to Young, 7 Aug. 1784). This refers to the Asgill affair of 1782. In retaliation for the hanging of a rebel captain by American loyalists, George Washington responded by having British POWs of the same rank draw lots for hanging. Charles Asgill was chosen, but in the end the American Congress set him free. (see Digital Encyclopedia of George Washington, Asgill Affair). Miles retired from the 17th and the army in November of 1789. He died without heirs in 1809. Family sources style him as Colonel Miles at the time of his death, but I have found no evidence of further service in the regular forces. (BLG 1862, Barton of Rochestown).

Two other officers, Alexander Saunderson and James Forrest, joined Gideon Shairp in 1781 and served until the end in 1783. Saunderson was yet another member of the Irish gentry. The Saundersons of Castle Saunderson, County Cavan, came over from Scotland in the early 17th century. Alexander’s father, Alexander senior, was head of the estate and served as High Sherriff of Cavan in 1758. Our Alexander was the second son (see BLG of Ireland 1904, Saunderson of Castle Saunderson). Unfortunately for him, his father, at least according to family lore, fit the stereotype of the wastrel Irish gentleman. He was a spendthrift and a gambler and spent much of his time racing horses at Curragh and elsewhere. Rumored to have been a member of the Hell Fire Club in the Wicklow Hills, he became a wanderer after Castle Saunderson was damaged by fire. (Henry Saunderson, “Saundersons of Castle Saunderson”, 1936). Our Alexander was born circa 1756. He entered the army as an ensign in the 37th Foot on September 30, 1775 and became a lieutenant in the same regiment on May 20, 1778. He came to the 17th as a captain on April 29, 1781, and was Captain of the grenadier company by July of 1781. In 1783 the regiment was reduced from twelve companies to ten as the British army returned to the peacetime establishment, and Saunderson, as one of the two junior captains, was put onto the half pay. With the coming of a new crisis in 1792 he found his way onto active service by trading his half pay for a captaincy in the 69th Foot on June 30th. Saunderson remained in the 69th for the remainder of his career, becoming a brevet major on March 1, 1794, a major on July 1, 1796, and a lieutenant colonel on March 30, 1797. He left the service in 1800, and died childless in 1803, leaving his estate to his wife Aurelia. (PCC Will proved 1803)

Finally, we have an American, James Forrest, one of possibly eight or more in the 17th during the period of the revolution. He was born in 1761, the year that James senior, his father, moved the family from Ireland to Boston, so our James may have been born in Ireland. His father was a prosperous merchant before the war and lost his fortune as a result of his loyalist support of the British cause (E. Alfred Jones, “The Loyalists of Massachusetts”, 1930). James senior raised the Loyal Irish Volunteers in Boston in 1775, and contributed two sons to the British forces. Our James joined the 38th Foot as a volunteer in 1777. Gentlemen without the money to purchase or the influence to find their way into the service often joined serving regiments as “volunteers”, hoping to be appointed to vacant commissions after proving themselves in the field. James was wounded while serving with the 38th at the battle of Germantown and was appointed ensign in the regiment in October of 1777. A letter James wrote in March of 1780 seeking a company in a loyalist corps expresses the frustration of those trying to get ahead without financial means: “I have not the most distant prospect of promotion in the 38th, the repeated misfortunes my Father has met with since the commencement of the Rebellion put it out of his power to purchase for me.” (Clinton Papers, Forrest to William Crosbie, March 3, 1780). Instead of transferring to the loyalist units he was appointed lieutenant without purchase to the 17th Foot on February 19, 1781 and seems to have joined the grenadier company about the same time as Saunderson. James Forrest retired as a lieutenant in September of 1788.

Dr. Mark Odintz

conducted his graduate work in history at the University of Michigan back in the 1980s and wrote his dissertation on “The British Officer Corps 1754-1783”. He became a public historian with the Texas State Historical Association in 1988, spending over twenty years as a writer, editor and finally managing editor of the New Handbook of Texas, an online encyclopedia of Texas history. Since retiring from the association he has been working on turning his dissertation into a book. He lives in Austin.

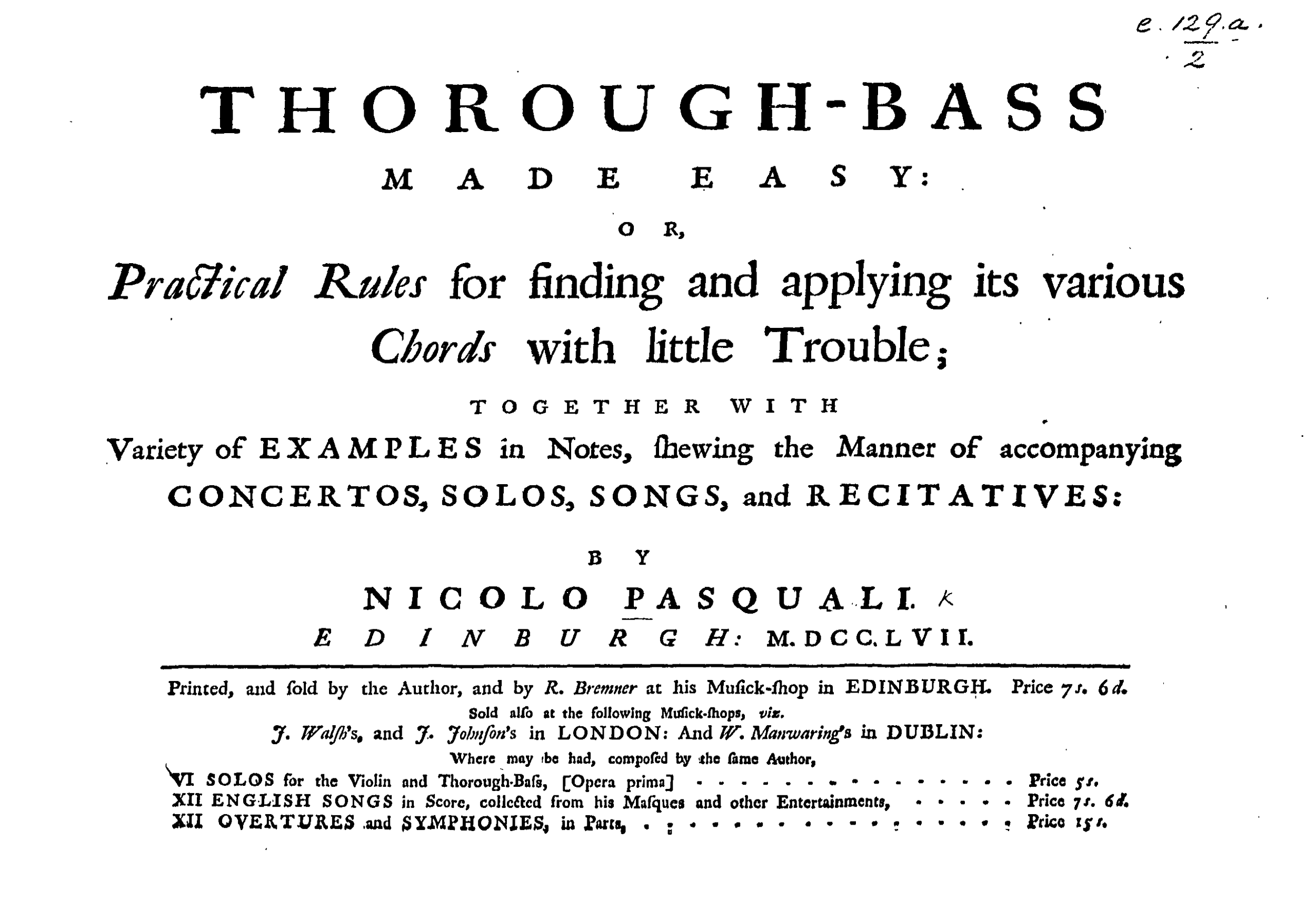

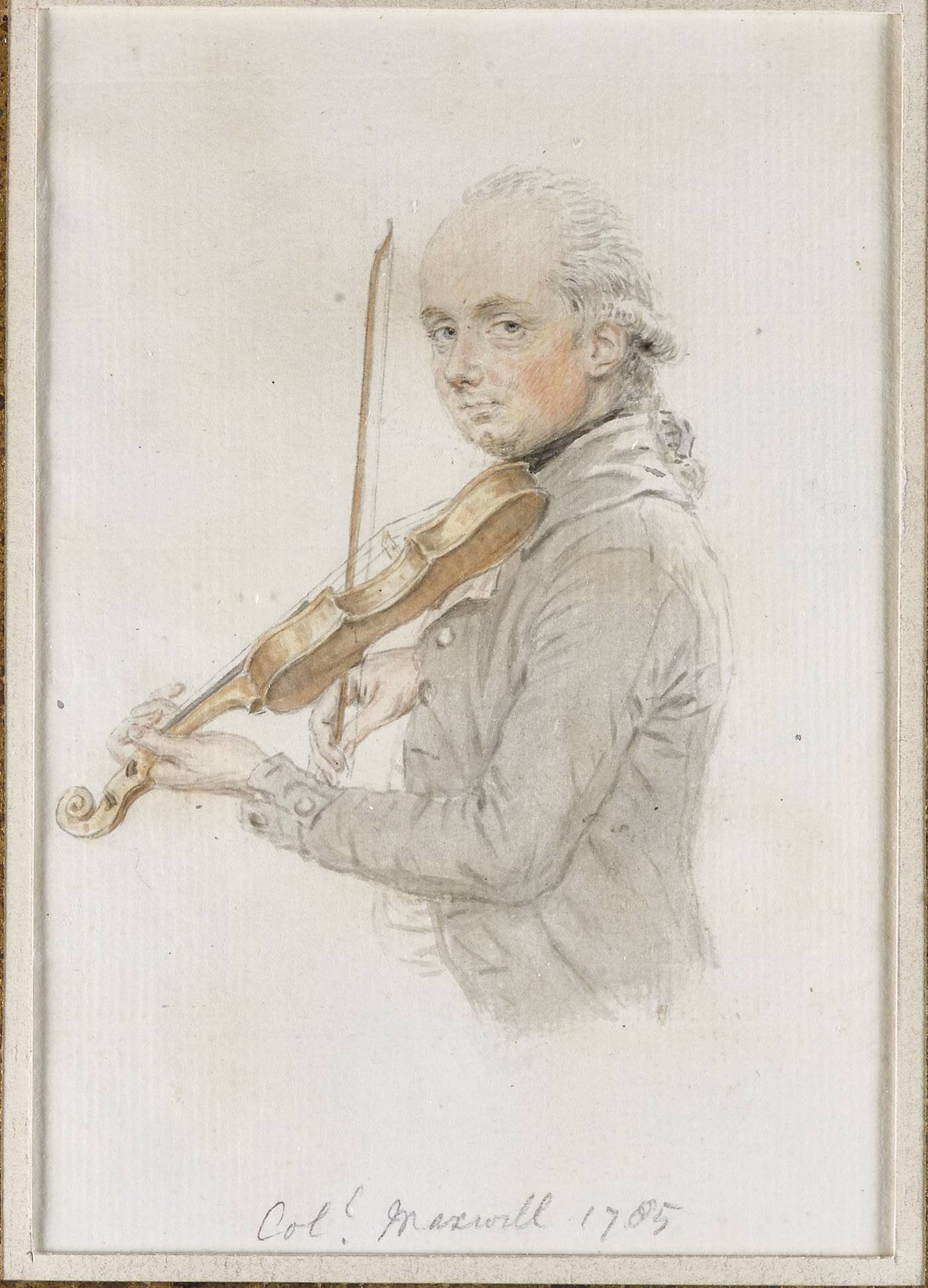

Music Made Easy: A Guide to Period Playing

As a folk music lover myself, I grew up around listening to jigs and contra style songs as my parents met and continued to go clogging when I was a kid. I'm very excited to introduce Tim MacDonald a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music and a good friend of mine. This post is filled with fun facts, images and tunes. Enjoy!

Mary - An attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry

And for this reason, in every age, the musick of that time seems best, and they say, Are wee not wonderfully improved? And so comparing what they doe know, with what they doe not know, they are as clear of opinion, as they that doubdt nothing.

~Roger North, ca. 1726

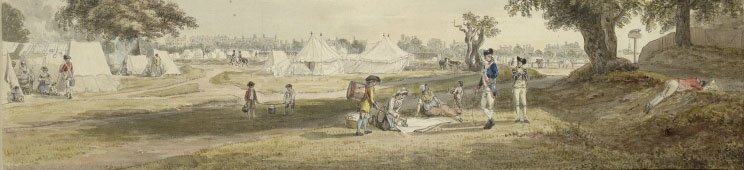

Much of the look of a recreated 1770s camp can be recreated faithfully with relatively obvious documentation. The tin kettle hanging over the fire was copied from an original excavated at a military site. The crossbar that it hangs on was chosen after reading a paper that analyzed dozens of images and other accounts of period military cooking. The stew boiling in it was based off of a documented ration issue and a description in a soldier's journal. And so on and so forth. Gathering, evaluating, and applying all of these sources requires a tremendous amount of insight and plain old hard work. But there's usually a sense of how your interpretation measures up. Does your coat match an original? Well done!

The sounds of that same camp, though, are much less concrete. In the 18th century as now, music was commonly-heard and well-loved. And in the pre-recording era, an even higher percentage of the population played an instrument, and musicians could be found everywhere from the drawing rooms of the upper class to the earth-floored houses of the lower class, from the taverns (many of which had loaner instruments available) to the  drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations:

drill of a North Carolina militia unit, which in July of 1775 featured "a very ill-beat drum and a fiddler, who was also in his shirt with a long sword and a cue in his hair, who played with all his might". But what did it sound like? Nobody will ever know for sure— there are (obviously) no surviving musicians and no recordings, and thus no guarantee that the modern performer will get it exactly right. But all is not lost. There's still a wealth of tremendously helpful documentation, and there's a lot of value in trying to get as close to a period sound as possible. Here are some considerations:

- Get the equipment right. Many common instruments of today didn't exist in their current form in the 18th century. Much as an M-16 rifle is no substitute for a Brown Bess, a modern

violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment.

violin, guitar, tin whistle, or similar is no substitute for a Baroque violin, cittern, or flageolet. Cataloguing period-correct instruments and describing their properties would fill up this entire blog post, but the information is easy to find (usually by Googling "baroque [name of instrument you play here]", then confirming with period accounts and artwork. Material culture still matters, and all your material culture research skills still apply. It's not just a simple matter of appearance or even acoustics: playing a period instrument instead of its modern counterpart dramatically changes how you go about making music on it. Returning to the firearm analogy, think of how using an M-16 instead of a Bess changes everything from the manual of arms to the tactics involved in fighting with it…that same level of difference exists between playing a tune on a modern, metal-strung violin with a concave hatchethead bow and a gut-strung violin with a convex pikehead bow. It's hard to progress unless you're using the right equipment. - Forget about folk music. It's very tempting to learn folk tunes, reflect on how there's an unbroken tradition of playing them that stretches back to the 18th century, and then play them unaltered at events. Resist this temptation. First of all, tradition slowly mutates things over time, and 240 years of mutation adds up to a lot. Second of all, the term "folk music" is fairly problematic in an 18th-century context: there was no distinction between "folk" and "classical" players, everyone played everything (limited solely by their skill level and the functions they were playing for).

- Play the right tunes. Many pieces we consider "old" today actually originated inthe 19th century, and many period-correct tunes have been forgotten about. Fortunately, there's a wealth of surviving tune collections in both published and manuscript form. They can be found online at IMSLP, archive.org, the websites of good libraries (such as the National Library of Scotland), and elsewhere, or in person at major libraries (research-oriented libraries are usually better than lending libraries) or the office of a friend already involved in early music. What collections to look for first? Try searching newspaper archives for publication announcements, period accounts for tunes mentioned by name or catalogues of music collections of notable people (such as Thomas Jefferson) or sites (such as Williamsburg).

- Play them the "right" way. The catch-all term for playing historic music is HIP: Historically-Informed Performance. As alluded to above, it'd be unfair to call it HRP (Historically-Replicating Performance) or similar because that's impossible. But there's a big difference between letting the I stand for "Informed" and letting it stand for "Ignorant". What to do? Read period treatises on music-making (I've listed a few popular ones here). Read modern commentary on the philosophy of 18th-century musicmaking (The End of Early Music and The Weapons of Rhetoric) are good places to start. Read about how the tunes were used. If they were played for dancing, try to recreate the dances. Play a lot, experimenting with different interpretations (and everything that entails: different affects, different tempi, different ornamentation…). Recreate period-correct ensembles (violin + cello and one-keyed flute + harpsichord are two easy and popular options). I've been amazed at how I used to dislike certain popular tunes but eventually found an interpretation that made it all make sense and led to really compelling music. It's hard, but it's well worth it.

- Display 18th century musical values. This is linked with #4. Throughout the 18th century (and before)—and much less so today—the following was prized in music: a) Composing one's own music. b) Personal interpretations of the music, fuelled by a heavy dose of improvisation (quoth Mozart in a 1778 letter: "[The performer should play] so that one believes that the music was composed by the person who is playing it.") c) So-called "rhetorical" playing: performing as if the music was a speech being presented in public, not just a string of notes. What does this mean? Phrasing appropriately (adding "punctuation" between the notes), changing dynamics (nobody speaks in a monotone), and cycling through various affects (even a eulogy isn't sad for its entire duration—it'll have sad parts and angry parts and even funny parts and happy parts and so much more).

This is a very brief introduction to a very complex topic, but I hope it points you in the right direction! Happy musicking!!

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo Tim Macdonald & Jeremy Ward. When not involved with some aspect of music, he can be found running silly distances, studying silly languages (currently Braid Scots), helping out at church, or mucking about at an AWI reenactment.

Tim Macdonaldis a professional performer and researcher of 18th-century Scottish fiddle music. He's recently returned from the Musica Scotica conference in Scotland, where he presented a paper on the life and work of composer Robert Mackintosh (1740? – 1807, and frequently performs with 'cellist Jeremy Ward as the creatively-named fiddle duo Tim Macdonald & Jeremy Ward. When not involved with some aspect of music, he can be found running silly distances, studying silly languages (currently Braid Scots), helping out at church, or mucking about at an AWI reenactment.

Listen to Tim Macdonald recreate the sounds of the 18th Century

Tim & Jeremy Live at the Midwest Sing & Stomp VIEWTim & Jeremy Live Wife Jigs VIEW

A Layman’s Guide to Historic Research

This week after a few weeks of rather heavy research and unit development blogs, writer Kyle Timmons joins us again to welcome back the website with a light hearted research blog. If you've missed the blog, it is back! Thanks for standing by us.

Mary Sherlock - An attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry.

Just a disclaimer to start off with: I AM NOT A HISTORIAN, HISTORY TEACHER, RESEARCHER, ARCHAEOLOGIST, OR ANYTHING LIKE IT. I am a simple person who enjoys history immensely and I’ve read and studied history much of my life. HOWEVER, I have the honor and privilege of being friend and acquaintance to many truly gifted and highly regarded Professional Historians. They’ve taught me so much about the 18th Century, the Revolution, and the British Army. But most importantly, they’ve given me the tools research on my own and to hunt down information that is of interest to me, and hopefully I can turn that information around and further benefit the hobby, the community, and our understanding of the 18th century. I’m going to take some time and share some of those tools with you.

- BE SUSPICIOUS. The moment that you read that previous statement is gone, and is never coming back. You can’t change it. But in an hour when you’re eating delicious food and playing on your phone you’ll likely forget about it. Maybe tomorrow you’ll share your memory of this blog with a friend, but you’ll share the points in your own words. You might get things wrong. 60 years from now when you’re telling your grandchildren how you first got into reenacting you’re memory of the antiquated computer or smart phone you used back then will be colored by nostalgia of the past.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

That’s how history is written. It’s mis-remembered, its colored by the writer’s opinion, maybe inflated by his need to tell a good story, or he’s recording it through hazy lens of old age. Whenever you read a historic source, always keep in mind who is writing it, his goal when writing, and his frame of mind, and when he’s writing. A journal entry or letter written the same day is a great source but even then things can get jumbled, misrepresented, summarized, etc. Your solution to this problem? Find more sources. 1 guy saying the British marched at the open order in battle in 1777 is an anomaly. 2 sources is a little better. 3 is better. Finding details that agree from opposing sides is even better. General Orders recorded in an orderly book detailing how the army is to be deployed just adds more ammunition to your theory.

- YOU MAY BE WRONG BUT YOU MAY BE RIGHT. The modern age we live in is actually an exciting time for someone with a history interest. That’s because high definition imagery and the internet are making it easy for someone in the United States to view an artifact or painting housed in England, or Germany, or anywhere else in the world in detail from the comfort of their home. Books, journals, etc. that are no longer in print or are one of a kind have likewise been digitized and can be accessed around the world either as open domain files or through special archives. This means information that has either laid unseen in a private collector’s library, or has only been accessible to a select few can now be accessed by the entire world. This tidal wave of new information is changing how we see the 18th century in numerous ways. A good example of this is the silk bonnet. Earlier it was commonly believed by reenactors that a silk bonnet was something that would have been out of reach to the “lower sort” of women in the 18th Now however, after searching through runaway ads here in America, looking at artwork from England, it’s clear that these beautiful articles of clothing were available to a much wider range of women than was originally supposed. Our knowledge of the 18th century is largely a collection of theories; strong theories mind you, and ones back up with multiple bits of data to support them. But as the data changes, our conclusions must change as well.

- IMAGINATION IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR KNOWLEDGE. Even without photographs, film, or with the amount of material culture items industrial-age historians are accustomed to there is a very large amount of source material and artifacts from the 18th There is no excuse for not making use of this material. When you choose an impression, be specific about what it is you’re trying to do. Are you doing a civilian or military? What nationality? What year and where are they? What is their social class? All of this is important. Military clothing, though it follows the fashions of the time, is distinct in many ways from its civilian counterparts. You won’t find examples of civilians in 1777 Philadelphia wearing gaitered trousers. The nation is important because every nation has their own idiosyncrasies. Time and place also play a factor. Fashions, like today, change with time.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Most military units have to get new clothing from year to year because their clothing wears out, just like yours does (though I doubt you’re marching for miles every day or sleeping outside in the rain!). That means they’re style of clothing is likely to change, either from fashion or from lessons learned on the battlefield. If the unit you’re recreating DIDN’T get their clothing issue than that in itself will change how you represent that unit.

Social class is also of major importance. Some clothing item are compatible to some extent across the classes. For instance, men’s shirts of the day are universally of a good quality in terms of stitch work (though they are often made of different grades of material). In other ways they’re very different. A laborer isn’t likely to be wearing a silk coat and breeches. Likewise, a gentleman isn’t likely to have an osnabrig (a kind of course natural linen) shirt and the same clothing items as a private soldier in the army (any army). Doing any impression costs money. To do a higher class impression well costs more money, just like how it’s easier to get a suit from Boscov’s (like me!) than to have one tailored to your desires in London or L.A.

- QUALITY IS A QUANTITY ALL ITS OWN. This is the last point I want to make. I’m immensely proud of my impressions, of which I have two…and a half. I have a 17th Regiment soldier’s kit, a kit for the Philadelphia Associators, and a mostly finished civilian impression. I say “mostly finished” because my coat is sitting sleeveless and partially un-lined on a chair. The reason I’m immensely proud of my kit is that I’ve made much of the clothing items I possess. My 17th Regimental and its waistcoat were the first 2 sewing projects I’d ever done. The things that I didn’t make were made by friends of mine who are very skilled at their trades. That’s what makes a good 18th century impression. Clothing of the time was done by hand, not machine, and most men’s clothing is fitted. You can see this in the paintings and sketches of the time. Clothing was expensive for these people, and they took care of what they had. They also dressed as well as they could. You should, too. If you’re new to this period, or reenacting in general, my advice for you is this. If you’re thinking of buy “off the rack” clothing, don’t. Save your money. Reenacting isn’t going anywhere. There are people out there who will take your measurements and whip you up a set of period clothing. Many of them are really good, and naturally they charge for that service. It might take you time to get that money together but the quality will be worth it and you won’t have to go and buy a better piece of clothing down the road.

If you have an aptitude for sewing however, or you can get with a group of people who know how to sew and can teach you, then you’re life probably just got a lot easier. With the right patterns for your clothing, patience, and help, you can make your own clothing for a much more agreeable sum of money. On top of that, you learn a valuable skill. And once you can sew, you can make yourself into anyone!

The study of history and the recreation of it is a noble hobby. But to do it right takes work, research, money and commitment. But most importantly, it takes networking with good people. That’s how I have learned so much, and really it’s the people we hang out and work with that make this hobby so great.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

KYLE TIMMONSis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

The Physicality of History

On this weeks blog, we have a story written by another good friend of mine whom I've known for many years now, Kyle Timmons. He recently became the Corporal of the 17th Infantry with his years of reenacting experience behind his belt combined with the real life knowledge of a Combat Medic with National Guard of Pennsylvania. Like many, the love of history propelled Mr. Timmons to join the National Park Service in 2016, continuing to educate those in history, for the benefit of future generations. If you've ever wondered what it was like to live in the history world all year round, continue reading...

- Mary Sherlock,an attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

The bitter cold of a Valley Forge winter. The parched heat of a Monmouth Summer. The fatigue of an all-night forced march. The smell of gunpowder and the weight of a Short Land Pattern Musket. These are all things you hear about when people bring up The American War of Independence. You can envision the half-starved soldier standing picket at Valley Forge, or of that same soul struggling through the night to put one foot in front of another on a forced march. TV and the internet make it easy to visualize the Revolution. It’s another entirely to experience it.

I’ve been a reenactor for about 12 years now, and I’ve been with the 17th since it’s reformation at the end of 2014. When I started, I knew virtually nothing about the Revolution except what middle school and “The Patriot” showed me. Since then I’ve learned A LOT through reading texts on the subject like McGuire’s “The Philadelphia Campaign” Volumes I and II, Spring’s “With Zeal and With Bayonets Only,” or Don Hagist’s “Wenches, Wives, and Serving Girls.” All of which in their different way help to paint the picture of America in the time of the War of Independence. Each is invaluable to my understanding of the period. But something is missing. Try as you might with creative use of adjectives and alliteration, you can’t feel the written word. General Cornwallis’ Flanking Column’s long march of September 11th 1777 at Brandywine has no context if you have no idea what it feels like to BE A SOLDIER OF THE 18TH CENTURY.

So what’s that like? I’m glad you asked!

In the 10 months or so from our first sewing party to our first official event in September 2015 we equipped 15 infantrymen. Each man was equipped with what the typical infantrymen wore on campaign. That is, a white linen shirt with ruffles sewing into the neck slit, a wool waistcoat, linen “gaitered trouser” that covers the shoes and hold them to the feet with a straps, a wool broadcloth regimental pattern coat with the regiment’s facing color, lace and buttons designating its wearer as a soldier of the 17th, a velvet and linen neckstock approximately the height of the soldier’s neck, and finally a felt cocked hat of the military fashion. All of these items are made to fit the man within and are quite comfortable, but the feel is definitely different from modern clothing. Now that you’ve got all this on let’s kit you out with the tools of the trade.

Over all of this comes your bayonet belt with your 14 inch bayonet slung over your right shoulder, on your other shoulder belt is your cartridge pouch loaded down with 21 cartridges, your tin canteen full of water, a haversack with three days of food stuffed in it, all of your earthly possessions rolled up in your blanket slung over your back, and of course your 11 pound musket. Once you get it all on you start to realize some things that a book doesn’t really tell you. You find that the cut of the coat and waistcoat kind of force you to stand somewhat straighter than usual and a brand new neckstock doesn’t like when you try to turn your head in any direction until you’ve sweated in it a few days and softened up the buckram layer that stiffens it. After your first hour in full kit the cross belts start to dig into your shoulders a bit and might further discomfort your neck. Ironically, you find that that heavy wool coat your wearing breaths rather well and isn’t nearly the death trap everyone said it was!

Now that you’ve got the clothes and the gear on, it’s time to actually do something! One of our events in 2015 was an “Immersion Event” in Virginia. What that means is we leave EVERYTHING from the modern world in the cars, there’s no public to view us, and for all intents and purposes we are going into the 18th century for 48 hours. This was in October or November and it was cold. The scenario was that we were to cover a fording point on a creek so forage parties could move back and forth.

We marched at dawn to the creek in question and as we forded it we took fire from rebels who were some 100-150 yards away atop a hill. Well, we dashed across the creek, consolidated our forces, and sprinted across the open ground to cover at the base of the hill. The handful atop the hill, not willing to meet British steel that morning, wisely yielded the ground. We climbed to the top of the hill and secured it. THEN began the work. We posted about half our number on piquet while the rest set to work felling trees for crude defensive barriers, wood for fires to cook our food and to dry our stockings and feet, and of course we built wigwams to shelter in that night.

That initial skirmish was the only real fight the entire day. The rest of the day we spent on work parties, standing picquet, or on patrols looking for rebel militia we knew to be in the area. When night fell so did the temperature and it began to rain. Greaaaaaat! Due to our limited numbers and the number of guard posts we had it was necessary for all of our men to take 2 separate 2 hour shifts on picquet. It absolutely sucked. It was hard to see anything more than 30-40 yards out and you knew that if the militia were out there you couldn’t see them. The wind was blowing too, which cut right through our coats. Some of our men shirked their duty to shelter around a small fire and nearly got caught by one of our sergeants. Thankfully, the rebels left us alone that night.

The next morning we ate our rations, drank black coffee done over the fire and broke camp. Everyone was in a foul mood by and large. We were tired, still kind of wet, and uncomfortable. The second time across the creek was done without a complaint because we knew we were marching to the cars. And then it was over.

But for the 18th Century Soldier, be them Loyalist or Rebel, that was just another day in the war! And it was a VERY long war. The 17th landed in November of 1775. They didn’t leave America until 1783. Those that lived that is. And they didn’t see England and home again until 1787! So for 8 years the soldiers we represent endured wartime hardship. They endured day after day after monotonous day of picquets, patrols, work parties, long marches, and occasionally the absolute terror of battle. They endured starvation, discontentment, barbaric punishment, poor pay, a hostile or at least untrustworthy local population, and the number one killer of them all: disease. And may I add there was no retirement plan in the 18th century and very few men who applied for military pensions got them.

All this brings two questions to mind. The first is: how? How did they do it? Were they tougher people back in the 18th century? I don’t know. The modern soldier faces struggles not all that different today. Why didn’t they quit? Again I don’t know. Many many soldiers deserted throughout the war on both sides. Those that stayed might have feared the punishment that waits for the captured deserter. Some I’m sure were true believers in their respective causes. Many, I’m sure, didn’t quit because they didn’t want to leave their buddies. A military unit is a family, particularly in the 18th century where men can spend their entire military lives among the same men in the same unit.

My second question is what I asked myself when I reached the far bank of the creek. Could I do it? Could I have endured the service back then? Could you?

-Kyle Timmons, Corporal, 17th Regiment of Infantry

Kyle Timmonsis a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he's pretty alright.

Opening a Window to the Past

Over the next couple weeks, I am happy to announce that there will be a series of guest bloggers who have kindly accepted my offer to write a little blurb about their experiences in reenacting and research. The 17th Regiment of Infantry hopes that the readers will find that they share a common thread with the guests and welcome them with kind thoughts and responses as they have so kindly taken their time to write. This week we have a wonderful friend, Jenna Schnitzer, who has taught us so much about women's history as we remember to commemorate all the women who came before us. Well with that brief introduction please read on! Let us know your feed back on social media or in the comments box below.

Enjoy,Mary Sherlock- An attached follower of the 17th Regiment of Infantry